With the last pair of squirrelers disappearing down the Alaska Highway in mid-October, another year has been put in the books for the Kluane Red Squirrel Project!

This year was a big one for us, as we marked 30 years since we marked our first squirrel pups in the project. For many of the grad students and technicians that worked this year, it’s literally a lifetime ago. The squirrelers-turned-pastry chefs made a cake to celebrate the occasion this spring. Nice work on the edible midden!

Stan Boutin celebrates 30 years of squirrel nest visits in the Yukon. Photo by Andrew McAdam.

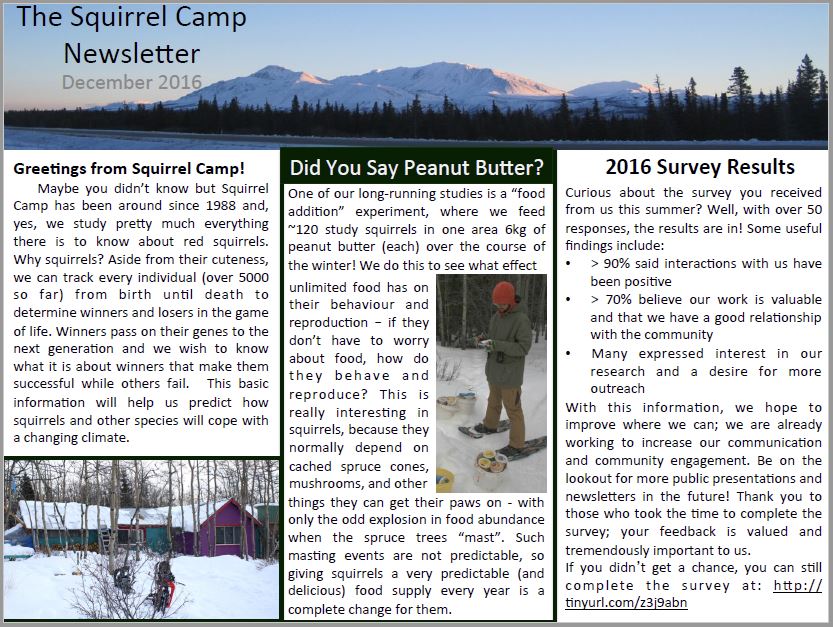

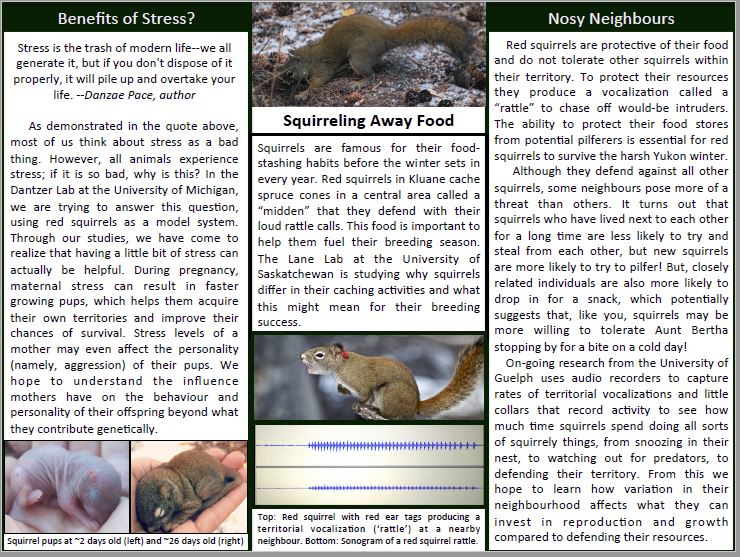

We had many diverse projects on the go this year in addition to the core work of the project. Sarah Westrick (Michigan) and team followed 48 mother squirrels as they reared their pups to investigate maternal care. Jack Robertson (Guelph) and team spent over 100 hours observing territory intrusions by nosy squirrel neighbours to understand social dynamics and effects of relatedness. Maggie Bain (Guelph) and team used the power of technology to record, analyze, and play back squirrel vocalizations to tease out the secrets of squirrel communication and determine if they can discriminate relatives from unrelated squirrels through bioacoustics. April Martinig (Alberta) and team followed the daily dispersal efforts of juvenile squirrels to identify the range of strategies young squirrels use to find a territory of their own. Andrea Wishart (Saskatchewan) and team quantified resource abundance on individual squirrel territories by measuring over 3500 spruce trees and observing squirrel caching behaviour to understand what drives variation in caching behaviour.

With the recent publication of Eve Cooper’s undergraduate thesis work (http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/1568539x-00003450), we have published over 85 scientific papers, with many more in the works. Outside of the field, many of the scientists took to the conference circuit to share our findings. We made appearances at meetings such as Wildlife70, Canadian Society for Ecology & Evolution, Animal Behaviour Society, Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology, and more!

Outreach to non-scientists is also important to us, and we had many highlights this year. We hosted short visits from school groups, ranging from high school students at Haines Junction’s St Elias Community School, to university students all the way from England’s University of Exeter. A lynx resident in the valley was filmed near our site and graced TV screens across Canada when it appeared in The Nature of Things’ Wild Canadian Year series this fall, showcasing some of the other wildlife familiar to us in the Yukon. A journalist from CBC Whitehorse chronicled life at camp and some of the graduate student research being done this fall. Many of us gave science talks at The Village Bakery in Haines Junction to both local residents and intrepid RV explorers who dropped in for their fill of good food and squirrel science.

A red squirrel searches for any remaining seeds to eat in an old open spruce cone. Photo: Andrea Wishart

As I write this end-of-year wrap up, I absolutely must acknowledge that none of this could be done alone, and that is especially true in this highly collaborative project. We would like to express our gratitude to Agnes MacDonald for continued access to her trapline and the Champagne-Aishihik First Nation for allowing us to do this work on their traditional territory. Many thanks to the head technicians this year (Jack Robertson, Matt Sehrsweeney, and Zach Fogel) who not only kept fieldwork running smoothly, but had a special knack for team building and leadership that shone as an exemplary model to learn from. Thanks to Brynlee and Ainsley for coordinating and supporting from Edmonton, and all of the PIs (Stan Boutin, Andrew McAdam, Murray Humphries, Ben Dantzer, and Jeff Lane) for dreaming big and making KRSP what it is today, and challenging us to pursue these research questions in their labs. Finally, thanks to each and every Squirrel Camp resident (including Hare and Lynx Crews) for continuing to make Squirrel Camp not only a research station, but a home. Thanks to the families, friends, and partners us field biologists leave behind for supporting us as we wander north.

Keep your eyes peeled for more updates as we reunite this December for our annual Squirrel Meeting to plan for next year.

To 30 years, and more!

– Andrea Wishart, PhD Student

October 27, 2017 in Saskatoon, SK